A renewed focus on growth is the antidote to these ‘interesting times’.

“May you live in interesting times” … delivered with a heavy dose of irony, this figurative English translation of a Chinese curse (“Better to be a dog in times of tranquility than a human in times of chaos”) sums up how many of us may be feeling!.

Back in 2006 the EU presciently published a paper on the recessionary effects of a pandemic in Europe. Its baseline scenario suggested a first-year fall in GDP of 1.6% with additional effects pushing this up to between -2% and -4%.

Two years later a financial crisis rather than a pandemic gave us a whole new perspective on recession. UK GDP shrunk by more than 6% between the first quarter of 2008 and the second quarter of 2009. This recession was the ‘deepest’ (in terms of lost output) in the UK since quarterly data were first published in 1955 and the economy took five years to get back to the size it was before the recession. A ‘once in a lifetime’ downturn.

Fast forward to 2020 and anybody whose lifetime is more than a ‘baker’s dozen’ will have now experienced two ‘once in a lifetime’ economic events. The latest baseline forecast envisions a 5.2% contraction in global GDP in 2020 – European real GDP is projected to contract by 7% and the UK by more than 11%. That 2006 EU prediction seems positively benign! We know it’s bleak, and only going to get bleaker.

Yes, there will be some ‘winners’ during this healthcare disaster but the impact on many many businesses around the world is chilling. That marketing spend gets slashed in times of economic uncertainty is just a truism, but businesses need a growth strategy now more than ever – hunkering down or going into hibernation until ‘winter’ passes is not a serious option.

The focus for businesses must be how to grow in economies experiencing unprecedented headwinds and for which – a vaccine notwithstanding – the coronavirus hangover is likely to be felt for some years yet. There are however causes for optimism.

The good news is that ‘the arithmetic of growth’ is pretty straightforward – encapsulated in the ‘where to play’ and ‘how to win’ questions … maintain your own customer base (and potentially increase the lifetime value of each customer), poach customers from competitors, and/or attract new customers to the category, then engineer the marketing Ps to deliver. Strategy, at whatever level, is about making choices. It’s deceptively simple!

But how should you translate this into an actual growth strategy – again when faced with that truism that marketing spend, and especially consumer insight budgets, get cut in times of economic uncertainty. Deepening our understanding of our consumer isn’t optional or a ‘nice-to-have’ – but with a greater focus on cost and budgets we need to be very sure of the ROI. How does one develop a growth strategy when under such unprecedented commercial pressure?

Firstly, think ‘agile’! and secondly don’t reinvent the wheel.

The last 9 months have demonstrated how ‘agile’ organisations can be … process bureaucracy has gone out of the window in response to this crisis. Agile organisations are fast, resilient, and adaptable and putting in place the building blocks of a growth strategy should similarly not be a long, drawn out, ‘drains-up’, exercise. It should also be a pragmatic and flexible process or system.

And the customer insight required is already, largely, there – if you choose to look for it. The amount of data available to your organisation has increased exponentially and shows no sign of slowing. You must have the ability to integrate and synthesize the plethora of information that is now available to you, to harness this to the task of solving the problem.

And while there may be some sort of quasi-scientific method that would deliver a solution – there isn’t time that there used to be to digest all this new information, as organisations are driving an agile agenda – which means faster, leaner decision-making and so rethinking the classic approach to problem solving you have to become comfortable with leaner and creative ways of adding value … to engage in effectual reasoning. This is about having a broad notion of where you are heading and adjusting on route. It is not worrying too much about the how but focusing on the ‘end game’. This contrasts with the more causal approach to business problem solving which required us to evaluate risk and proceed in a more cautious way.

Early in 2020 we were embarking on growth strategy project for a UK based multi-national. Lock-down #1 threw everything up in the air – timetable, budget and process.

It would have been easy to just pull the rug on the entire project, but to their credit the leadership team decided that a growth strategy would provide a pathway through the coming recession and set the business up for success longer term. And it would get proper focus – the CEO mandated that “this is not an ‘at-the-side-of-the-desk’ effort”

However, compromises had to be made. Instead of traditional qualitative and quantitative and a process taking circa 6 to 8 months, we quickly arranged a wider pool of internal stakeholder interviews and a deep review of internally held data, while in parallel arranged 50 qualitative interviews with their own customers and non-customers identified through ‘connections’. Our work is always highly collaborative which appealed to a client team very keen to get involved in all aspects of the process.

Was it ‘perfect’? No. Did it work? Yes. It took 3 months to conduct the interviews, integrate this information with the organisation’s existing data, develop the initial frameworks, identify future growth opportunities and agree on customer priorities. And with these foundations the business could hone its ‘brand benefit’ and develop its capability road map – those elements needed to be in place to deliver its differentiated product offer to its target customers.

“The work has gone down brilliantly with the board” CEO

“A great team effort and great team result” Chief Commercial Officer

In developing this key framework, everybody bought into the fast, adaptable and resilient mantra – and in this same spirit redefined what was acceptable vis-à-vis the data, information and knowledge that they would work with … looking with fresh eyes at the value of what we might call non-traditional data.

Developing a growth strategy doesn’t always need ‘new’ data – in our experience organisations sit on a treasure trove of under exploited data, information and knowledge – conventional and unconventional. This ranges from, previously collected, quantitative and qualitative data, behavioral and sales data and the relevant experience and market knowledge of key stakeholders within the business.

Tapping into this enables you to unearth nuggets of insight at a fraction of the cost of a new research project. Organisations should ‘squeeze this orange’ for all it is worth.

Now in today’s environment, the ground may have fundamentally shifted, and so what we learnt yesterday may not help us understand today – but by marshaling what we know, we can ensure that any new data that needs to be collected or areas to be explored are focused laser like on the issues at hand – short and sharp – we are not spending any time reinventing the wheel. This saves both money and time

The organisations that succeed (and maybe thrive) during and after this pandemic will be those organisations which truly ‘know what they know’ and pragmatically apply this knowledge in a fast, resilient, and adaptable way to identify future choices and a winning strategy.

Riding the data avalanche! An opportunity for everyone.

Data-driven knowledge businesses are 23 times more likely to acquire customers than those which are not[1] and insight-driven businesses are growing at an average of 30% each year; and this year (pandemic aside) they would be taking $1.8 trillion annually from their less-informed industry competitors[2]. Businesses big and small sit on a mountain of underused data – the good news is that tapping this potential is not hard.

As the common refrain goes, data is the new oil. It’s easy to see the parallels – data, like oil once was, is a vast, largely untapped asset. In its raw form it can be messy, confusing and difficult to work with, but is immensely valuable once it has been extracted and processed.

However, the analogy can only be taken so far. Data, unlike oil, is effectively an infinite resource – with the total volume of data out there roughly doubling every couple of years. While known oil deposits are projected to run out in around 50 years, at the current rate the volume of data is expected to increase by a factor of over 30 million in that same time period.

Here’s an interesting thought … more data has been generated in the last ten minutes than ever even existed before 2003.

There is no sign of this data avalanche slowing down either. The “internet of things” means that in the not-so-distant future we may have every single electronic object generating data, and there may even be new types of data we haven’t even considered yet. It’s more important than ever for businesses to understand their data and, more importantly, what they can do with it.

Data has fostered new innovation, and new innovation has created more data! Amazon have changed the way we consume by using sophisticated AI recommender systems, which take data from all of their users to tell each individual what they should be buying or next, replacing the human curators they used in their earlier years.

Some companies have gone even further, turning the data they collect from their customers into their primary asset. We all know that Facebook and Google do not charge you money to use their various features, but instead collect data about you, which, when aggregated with millions of other users and sold to third parties is a far more sustainable and profitable business than trying to get people to pay a subscription to the services they’ve used for free, for years.

These companies are huge and therefore benefit from a massive user base who are constantly providing vast amounts of data which they can work with … and have developed many cool tools to interrogate it.

The volume of available data means that even the simplest of operations can benefit from at least dipping a toe into the data universe and tapping the value of the insight that lays within it. How an organisation uses its data will be a key point of difference between organisations that maximize their potential and those that do not. Really successful organisations will be knowledge-based organisations.

And you don’t necessarily need the latest technologies, or an army of data scientists, to take advantage of this data bounty. In our experience organisations sit on a treasure trove of under-exploited data, information and knowledge. This ranges from previously collected hard research data as well as behavioural or transaction data collected from a range of sensors to the relevant experience and market knowledge of key stakeholders within the business. Tapping into this enables an organisation to unearth nuggets of insight at a fraction of the cost of a new research/data collection project.

As far as existing data is concerned, you should ‘squeeze the orange’ for all it is worth.

From a purely consumer research/insight perspective – all too often businesses keep outputs and work product from previous projects but don’t see the value in the raw data – but it’s yours, you have paid for it and it can be put work. Now in today’s environment, the ground may have fundamentally shifted, and so what we learnt yesterday may not help us fully understand today – but by marshaling what we know, we can ensure that any new data that needs to be collected or areas to be explored are focused laser like on the issues at hand – short and sharp – we are not spending any time reinventing the wheel. This saves both money and time

An open mind, an inquisitive attitude and some creative thinking are all that’s needed to get started – as well as a capability that we like to refer to as ‘sense-making’ (Pirolli and Card 2005) … which is the ability to quickly get to grips with the wide and potentially overwhelming panorama of data, information and knowledge available … bringing this together into a coherent whole to inform choices and decisions

Knowledge based organisations must have the ability to integrate and synthesize the plethora of information that is now available, to harness this to the task of solving the problem. And while there may be some sort of quasi-scientific method that would deliver a solution – there isn’t time that there used to be to digest all this new information, the agile agenda means faster, leaner decision-making and so rethinking the classic approach to problem solving means becoming comfortable with leaner and creative ways of adding value.

Whilst we’ve touched on the benefits data has brought to big organisations, no business should feel that size is a barrier to entry in exploring the opportunities in data. In fact, it is the smaller organisations that might reap the biggest rewards – in relative terms at least – since intelligent use of data is more likely to offer a competitive advantage.

A longitudinal interventionist study conducted by UC Berkeley on a Café based in Copenhagen[3] demonstrated how detailed data collection– leading to data-driven decision making – could oversee an sixfold increase in turnover over a seven year period. This did not require and fancy software or expert data scientists – it was simply a matter of recording the numbers – having the right sensors in the ground – to gather actionable data that clearly expressed how the Café was performing against various KPIs and ensuring that the findings – and the implications of those findings – were acted upon. By embedding this ‘wide-angled lens’ approach into the ‘DNA’ of the organisation, the impact of decision-making was consistently understood in terms of data.

“For Sokkelund the implementation led to real-time data on operations e.g. sales per seat per day, or per customer, as well as customer retention data. Understanding this data is crucial; for example, when the chef decides to change the menu, or when tracking the effects of marketing. Having access to such small data makes it possible to track small improvements to the business model … these changes not only led to cost reductions, but lowered customer acquisition costs, improved customer retention and added new revenue channels”

This process was termed as a “small data transformation”, which highlights how really anyone who can utilize data to their advantage. ‘Small data’ can be just as powerful as ‘big data’ in the right context, and it’s about finding the right approach for your business, rather than chasing the latest and greatest trend.

Collecting and collating corporate knowledge isn’t hard. To help our clients on the journey to becoming knowledge-led organisations, Decision Architects have developed the Surge3 platform – which is a knowledge ecosystem bringing together what an organization knows into a single hub so that it can be efficiently and effectively collated, interrogated and analysed.

- It offers a system for collecting, collating and integrating raw market research data and the ‘product’ from market research projects, to provide a central hub where the ‘corporate research memory’ can be accessed, making ‘corporate knowledge’ visible and searchable

- It fosters collaboration between individuals and groups on areas of shared interest – by tagging ‘who has worked on what’. Users can identify colleagues with topic expertise, learning from their experience rather than ‘reinventing the wheel’

- It create new recombinant value by combining disparate data (from previous research studies), to create new information, knowledge and insight

Effective data integration and management is at the core of Knowledge Organisations – at a minimum actioning internally generated data – making it integral to decision making. Once you have this foundation, adding in additional streams of external data then provide a powerful platform from which you can build sustainable competitive advantage.

To find out more email neil.dewart@decision-architects.com

[1] https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/marketing-and-sales/our-insights/data-driven-marketing

[2] https://www.forrester.com/report/InsightsDriven+Businesses+Set+The+Pace+For+Global+Growth/-/E-RES130848

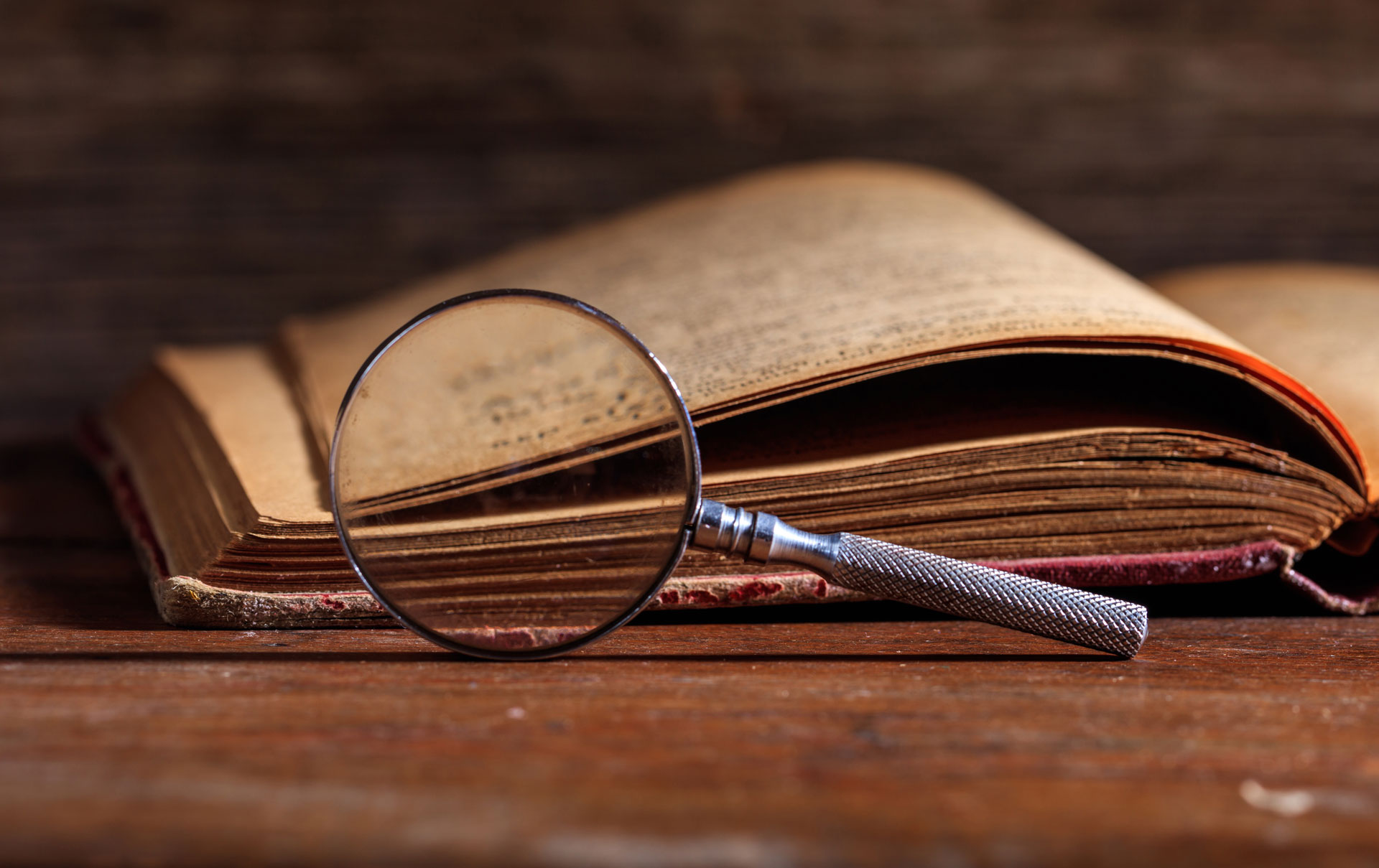

The Ongoing Battle For Your Mind

Another in our occasional series of blogs in which we will revisit some of the articles that we have found most useful over the years. This week we are going to focus on Ries & Trout’s three 1972 Ad Age articles ‘The Positioning Era Cometh’; Positioning Cuts Through Chaos’ and How To Position Your Product’ and their subsequent 1981 book ‘The Battle for Your Mind’.

“I studied [‘The Battle for Your Mind’] as an undergraduate in the 1980s and the fact that it is one of the few books I can remember nearly 35 years later … both for its content and cover –iconic brands bursting out of a man’s head in glorious technicolour – is a testament to its impact, and that it is still relevant today speaks to the importance of the message” Adam Riley, Founder, Decision Architects

Ries and Trout opened their 1972 articles with an observation that “[in today’s market] there are just too many products, too many companies [and] too much marketing ‘noise’. Yes, that was 1972 … (plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose).

To succeed they argued a brand had to create and own ‘a position’ in the consumer’s mind and cited Wednesday April 7, 1971 as the day the marketing world changed. David Ogilvy had taken out a full-page ad in the New York Times to set out his new advertising philosophy and outlined 38 points that started with ‘the results of your campaign depend less on how we write advertising than on how your product is positioned’.

Ries and Trout charted the evolution from the 1950s product era to the 1960s image era to the 1970s positioning era – which addressed the challenges posed by the ‘new’ over-communicated to, media-blitzed, consumer. Their work described how brands should take or create a “position” in a prospective consumer’s mind … reflecting or addressing its own strengths and weaknesses as well as those of its competitors …vis-à-vis the needs of the consumer.

And while positioning begins with the product – the approach really talks to the relationship between the product and the consumer … and by ‘owning’ some space in the mind of the consumer – by being first or offering something unique or differentiated – a brand can make itself heard above the clamor for attention – in their words – wheedling its way into the collective subconscious.

Ries and Trout laid out ‘How To Position Your Product’ with six questions …

- What position do we own? The answer is in the marketplace

- What position do we want? Select a position that has longevity

- Who must we ‘out-gun’? Avoid a confrontation with market leaders

“You can’t compete head-on against a company that has a strong position. You can go around, under or over, but never head-on”

- Do we have enough money (to achieve our objective)?

- Can we stick it out (in the face of pressure to change / compromise)

- Does what we are saying about ourselves match our position?

Its then easy to see the DNA of these questions in the ‘choices cascade’ set out by Monitor Alumni, Roger Martin, and P&G CEO (President & Chairman), A.G. Lafley, in their 2013 book ‘Playing to Win’ … the ‘where to play’, and ‘how to win’ questions culminate in a positioning – whether you call it a ‘benefit edge’ or a USP … it is a statement of position and is at the core of our growth methodology.

Just re-reading the 1972 articles you get both a fascinating insight into the marketing environment of 50 years ago, but also a sense of how relevant these articles are to contemporary marketing practice.

www.ries.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Positioning-Articles002.pdf

“For anybody interested in the psychology of consumer behaviour, Ries and Trout’s work really made the marketing discipline a lot more interesting, and as a student in the 80s their book really ignited my interest in marketing strategy and insight … what we used to call market research!” Adam Riley, Founder, Decision Architects

NPS and the Customer Satisfaction Jigsaw

Since it was first introduced by Fred Reichheld in 2003 (“The One Number You Need to Grow”, Harvard Business Review) to help measure customer satisfaction … the Net Promoter Score (NPS) has grown to become a crucial tool in the marketer’s arsenal.

The reason that NPS has been so successful and, in many ways become the go to customer satisfaction benchmark, is its simplicity – the ease and speed with which it can be asked. This means that it can be asked more regularly, limit the time that customers need to spend providing feedback, (because as much as we would like them to, not everyone wants to take part in a 20 minute survey once a month!), and it does not require any kind of math degree or statistical tool to analyse.

While many companies, big and small, use NPS as a performance index to evaluate the state of their brand, it is not without its critics for whom it is not specific enough, relied on too heavily by companies and difficult to translate into action. Used properly it can be a helpful metric, but there are a few noticeable caveats which, to garner maximum value from any customer satisfaction program need to be understood and accounted for.

So what should marketers be doing when implementing customer satisfaction to ensure maximum value?

A key starting point is to create a customer interaction plan. Engagement with the right audiences at the right times during the customer journey, as well as at the right frequency to obtain an accurate read on customer sentiment is crucial. Mapping and understating the key stages of this process will enable us to see where we are doing well and where there is the most room for improvement.

To harness the full power of NPS we then need to link up the scores provided with any other information that we hold on customers. This may not always be possible, but a well managed CRM system can enable us to dive into satisfaction scores much more deeply, looking at where the brand is performing well and how we are performing within key segments, cohorts or demographics. Another key benefit of this approach is that we can link satisfaction scores to other key business metrics allowing us to assess the tangible value that an increase (or decrease) in satisfaction score might bring.

We need to look at how we can ‘move the bar’ and increase scores, a point at which many a marketer we have spoken to have found challenging. Beyond purely looking at scores by stage of the customer journey this is the point at which text responses can provide real additional value. By focusing these on what the company could be doing better for all customers (rather than a traditional and not always that useful ‘Why did you give this score?’) we can look to explore key themes for improvement among both promoters and detractors of the brand. Many companies with successful customer satisfaction programs will also take the opportunity at this stage to engage directly with customers to understand their scores, and this can add an additional layer of value by tapping further into the voice of the consumer.

Finally, and arguably the most crucial stage of the process is feeding these responses back into the business, to create a Satisfaction Cycle that empowers the broader business to make tactical changes and improvements to products and services based on 4 key elements:

- Which improvements are we able to make?

- Which audiences would benefit most from these changes?

- How valuable are they to us as a business? (linked to key business metrics)

- What can we do in the short term and what are longer term goals

So is this ‘The One Number You Need to Grow’? That is certainly up for debate. To implement growth plans, any business needs much more information than the NPS on its own provides. It is no golden goose and gives us only a point in time satisfaction score. To harness the power that a well-formed customer satisfaction program can bring we must use it in the right way as part of a range of tools that can measure, identify and most importantly enable us to improve the customer journey. Knowing that customers would recommend our brand is great, but knowing what we can do if they don’t and how to improve the scores across key audiences is where NPS can deliver its true value

In praise of the ‘Diffusion of Innovation’

Another in our occasional series of blogs in which we will revisit some of the articles that we have found most useful over the years … these are the articles that can always be found on desks in the Decision Architects office. This week we are looking at Everett Rogers’ 1962 work on Diffusion of Innovations (and yes, it’s a book not an article).

“This model provides an intuitively simple lens through which we can look at how consumers approach any sort of NPD – it is not without its critics but it is a useful short-hand which we often apply to (say) a segmentation framework to talk to the propensity of different segments to try or adopt a new product or service …. be that a new delivery format for hot drinks, a new insurance concept or some form of health tech” James Larkin, Decision Architects

The foundations of this now ubiquitous framework are interesting. Rogers’ 1962 book was based on work he had done some years earlier at Iowa State University with Joe Bohlen and George Beal. Their ‘diffusion model’ was focused solely on agricultural markets and tracked farmers purchase of seed corn. It was Iowa, and Rogers was professor of rural sociology!

The diffusion model’s signature bell curve identified

Innovators: Owned larger farms, were more educated and prosperous and were more open to risk

Early Adopters: Younger and although more educated were less prosperous but tended to be community leaders

Early Majority: More conservative but still open to new ideas – active in their community and someone who could influence others

Late Majority: Older, conservative, less educated and less socially active

Laggards: Oldest, least educated, very conservative. Owned small farms with little capital

Between 1957 and 1962 Rogers’ expanded the model to describe how new technology or new ideas (not just seed corn) spread across society, but whilst Rogers initial work assumed that technology adoption would spread relatively organically across a population in practice there are barriers that can derail mainstream adoption before it has begun. The expansion to this frame discussed in Geoffrey More’s 1991 book ‘Crossing the Chasm’ highlighted a critical barrier to widespread adoption. This Chasm exists between the early adopter and early majority phases of the framework and to successfully navigate requires an understanding of the personality types that form the 5 fundamental building blocks of the model.

Innovators are happy to take a risk and try out products and services that may be untested or ‘buggy’. They look at the potential, do not expect things to be perfect and are happy to work with companies to improve initial offerings, a fertile testing ground for new technology. Early adopters in contrast are more tactical in their adoption. They want to be at the forefront of new technology but will have conducted their own research to evaluate the likelihood that the product will offer them tangible value. They are also more fickle, and are more likely to leave a product or service that is not living up to what was promised creating a potential void between them and the early majority.

Once we start to look at the early majority and beyond there is marked shift towards using something that ‘just works’. They are less interested in something new or shiny but, as the Ronseal advert would put it, something that ‘does exactly what it says on the tin’.

Seth Godin put it well in his 2019 blog when he said:

“Moore’s Crossing the Chasm helped marketers see that while innovation was the tool to reach the small group of early adopters and opinion leaders, it was insufficient to reach the masses. Because the masses don’t want something that’s new, they want something that works, something that others are using, something that actually solves their productivity and community problems.”

At its basic level the innovation adoption curve is a model that can be used to critically assess the appetite to adopt something new within a particular audience (be that segment, cohort or among a more general population). This provides us with a crucial framework element addressing the ‘where to play’ question … which we talk about so often with our clients and to enable the prioritisation of resources where they will have the biggest impact on growth and revenue

To go beyond the innovator and early adoption phases, products and services must deliver on their early promise, be built around customer needs improving on what went before. Getting there first can be a huge commercial advantage but failing to understand your audience and adapt accordingly can be the difference between wide-scale adoption and, at best, obscure appeal.

Why ‘new normal’ will look a lot like ‘old normal’

Since March my mailbox has been inundated with new surveys, trackers, consumer trend evaluations, and ‘thought pieces’ on the ‘new normal’. The world we live in from this point on will look nothing like the world we have known … so says their collected wisdom! If one was a cynic, one might argue that sowing doubt and uncertainty about the future reinforces the need to spend budget on consumer insight at a time when client businesses are looking to conserve cash and agencies are feeling the pinch – and this is my business as well, so I am not going to argue with the importance of maintaining ‘sensors in the ground’!

But if you believe all that you read we are facing a foreign landscape with consumer behaviour turned on its head! But with some trepidation … can I be the small voice in the crowd that says actually I believe that the future is going to look much more like the past than many would have us think.

Now I will caveat that with the future when viewed from the pre-Covid world was going to look different (that’s just a truism) … the migration from the high street to the virtual street perhaps being the most notable trend – and the pandemic has moved this process on (if for no other reason than such a precipitous fall in revenue would be difficult for any business to cope with especially those with a poor online presence).

Perceived wisdom is that the pandemic moved digital migration forward 5 years … as people have been forced to shop online, socialise with friends and family members online, to bank online, see their doctor online etc. And some of these behaviours are here to stay as sub-optimal customer experiences in a pre-pandemic world can now be seen as such by a wider group of consumers – who really wants to queue for 20 minutes in a bank branch or sit next to (other) sick people in a doctor’s waiting room. OK, some people will, but broadly speaking the pandemic has shown those of us who are not innovators and early adopters a better way in some areas.

However, the ‘new normal’ is not actually ‘normal’ and will meet the headwinds of behavioural inertia or the tendency to do nothing or to remain unchanged. The majority of us will go back to an office, and probably 5 days a week. We will start shopping in stores again – because we like physical (as opposed to virtual) shopping, and so the home will become less of (not more of) “a multi-functional hub, a place where people live, work, learn, shop, and play” (‘Re-imagining marketing in the next normal’ McKinsey, July 2020). We will want to travel again as soon as possible – the ‘staycation’ was fine, but we won’t want to make a habit of it, and our new found sense of ‘community’ will wane when the pressures and time requirements of everyday life kick back in.

I am not saying that there won’t be any change and I am not just sticking my head in the sand and hoping the current crisis would just go away. But consumer behaviour is akin to an elastic band … Covid-19 has pulled it in all sorts of different directions, but fundamentally it wants to ‘ping back’. When we have a few years post pandemic perspective, I suspect covid-19 will be seen to have caused a mild bump in the overall evolution of consumer behaviour … there won’t be a ‘new normal’ that looks very different from the ‘old normal’.

Katy Milkman – a behavioural scientist at Wharton was reported in The Atlantic as saying that new habits are more likely to stick if they are accompanied by “repeated rewards”. So if the threat of the virus is neutralised the average person will go back to a routine and at the moment the pandemic looms large because its our everything. While there will be some behavioural stickiness – its easy to overestimate the degree to which future actions will be shaped by current circumstances.

In praise of ‘Marketing Myopia’

In this occasional series of blogs we will revisit some of the articles that we have found most useful over the years … these are the articles that can always be found on desks in the Decision Architects office. The first of these is Marketing Myopia, published in the Harvard Business Review in 1960, chosen by Adam Riley.

“I love this article … it talks to the ‘where to play’ and ‘how to win’ calculations that we have at the heart of our work … and I reference it time and time again. And when we use examples of obsolescence … Kodak, Nokia, Blackberry etc etc. you can see in their downfall a failure to heed the lessons of Marketing Myopia. Levitt was one of the giants of our trade”

In 1960 Theodore Levitt … economist, Harvard Business School professor and editor of the Harvard Business Review, published ‘Marketing Myopia’ and laid the foundations for what we have come to know as the modern marketing approach. Levitt, one of the architects of our profession, popularized phrases such as globalization and corporate purpose (rather than merely making money, it is to create and keep a customer). The core tenet of his ‘Marketing Myopia’ article is still at the heart of any good marketing planning process or submission. In this article Levitt asked the simple but profound question … “what business are you in?”

He famously gave us the ‘buggy whips’ illustration…

“If a buggy whip manufacturer defined its business as the “transportation starter business”, they might have been able to make the creative leap necessary to move into the automobile business when technological change demanded it”.

Levitt argued that most organisations have a vision of their market that is too limited – constricted by a very a narrow understanding of what business they are in. He challenged businesses to re-examine their vision and objectives; and this call to redefine markets from a wider perspective resonated because it was practical and pragmatic. Organisations found that they had been missing opportunities to evolve which were plain to see once they adopted the wider view.

Markets are complex systems. The ability to successfully define, and to some extent ‘shape’, the market you compete in today – and will compete in tomorrow – is the foundation of good marketing. It is critical first step to maximizing business opportunities and identifying those competitive threats that may imperil the long term prospects of the business – or change the rules of the game to make its products or services irrelevant.

Senior management must ask, and marketers must be able to answer, the question … as a business, ‘where should we play’? This means defining the market in which we will compete – and being able to give size, scope, growth rates, competitive landscape, key drivers and barriers to success within it, as well as an appreciation of customers needs today – which are being fulfilled -and those unmet needs which may shape the definition of the market tomorrow. Market definition is not the same as ‘segmentation’ – but it is a necessary pre-cursor

When identifying ‘where to play’, marketers must address how to redefine our market to create a larger opportunity, or one which we are better positioned than the competition to take advantage of? How could our competitors reshape the market to their advantage and what impact would this have on us? And how will external trends – be they political, technological, social, economic etc. – reshape the market and affect our success? Many marketing questions then flow from this market definition – what attractive customer segments exist, how do we develop and deploy our brands against attractive market opportunities, what capabilities do we have today that give us competitive advantage, and what capabilities will we need tomorrow to sustain this.

At the time of his death in 2006, Levitt (alongside Peter Drucker) was the most published author in the history of the Harvard Business Review, and in a interview he gave about his published work, he said “In the last 20 years, I’ve never published anything without at least five serious rewrites. I’ve got deep rewrites up to 12. It’s not to change the substance so much; it’s to change the pace, the sound, the sense of making progress – even the physical appearance of it. Why should you make customers go through the torture chamber? I want them to say, ‘Aha!’”

An interesting segmentation that goes beyond elephants and donkeys – lessons from the US electorate

An interesting new report looking at the US political landscape was published this week (see the end of this article).

Why interesting? It’s a good example of a nice-looking segmentation – examining American public opinion through the lens of seven population segments. The report’s authors describe these segments as “America’s hidden tribes” – hidden because they have shared beliefs, values, and identities that shape the way they see the world, rather than visible external traits such as age, race or gender. By avoiding the use of demographic information or other observables – the authors contend – segments go beyond conventional categories and identify people’s most basic psychological differences.

The tribes identified are:

- Progressive Activists: highly engaged, secular, cosmopolitan, angry.

- Traditional Liberals: open to compromise, rational, cautious.

- Passive Liberals: unhappy, insecure, distrustful, disillusioned.

- Politically Disengaged: distrustful, detached, patriotic, conspiratorial.

- Moderates: engaged, civic-minded, middle-of-the-road, pessimistic.

- Traditional Conservatives: religious, patriotic, moralistic.

- Devoted Conservatives: highly engaged, uncompromising, patriotic.

“Essex man” was an example of a type of median voter that explained the electoral success of Margaret Thatcher in the 1980’s. The closely related “Mondeo man” was identified as the sort of voter the Labour Party needed to attract to win the election in 1997

Now there’s nothing new about political segmentation – whenever an election looms, someone produces a segmentation of the political landscape, and the media get over excited. In the UK this has famously resulted in Essex man, Mondeo man, Worcester Woman etc. All of these shed interesting insight on a phenomenon BUT, as with commercial segmentation, there is usually practical limitation on their application.

This latest US report cites its ultimate aim as “identifying the most effective interventions that can be applied on the ground to counter division and help build a renewed and more expansive sense of American national identity”. But how are these interventions supposed to happen? How do you intervene with the ‘Passive Liberal Tribe’? Put simply, how do you find them?

We’ve discussed before how the dissatisfaction with the outcomes of segmentation has risen, as the mix of effective marketing levers that an organisation has at its disposal has proliferated. The rise of direct-to-consumer, and the increasing importance of targeted communication and the use of databases has mean that the ability easily identify a segment (rather than relying on the customer to self-select) has become a crucial success factor.

The inability to effectively ‘target’ segments is at the crux of much of the dissatisfaction with segmentation. I have no doubt that this work on ‘tribes’ includes a complex algorithm to determine segment membership but these are difficult to action as the criteria for segment membership are complex and often difficult to replicate. How do you find the segments in the real world? While it is possible to profile these clusters after they have been created, as they have done with the ‘tribes’, often the results are less than clear cut.

This is less of an issue when you are using ‘above the line’ communications to communicate a political (or commercial) position, but increasingly organisations want to target their communication activity, undertake ‘direct-to-consumer’ advertising (for example) and locate these segments in their CRM database. An actionable segmentation allows us to better address strategic ‘where to play’ questions i.e. which voters (or customers) to focus effort on, their relative priority, and the opportunity they represent … as well as tactical ‘how to win’ questions i.e. what activities or messages are most likely to achieve our objectives in priority segments.

For those of us who don’t get to vote in US elections, all of this can be something of a spectator sport – but if you have a professional interest in segmentation and marketing frameworks – it raises interesting questions. While the ‘tribes’ segmentation is intrinsically interesting and insightful – too often in the commercial world we find that this type of analytical methodology limits the ability to identify “the most effective interventions that can be applied”.

‘Segments of One’ – myth or reality?

How many segments is too many? At some point we always have this conversation. Clients usually find 4 too few and 12 too many (leave aside that it’s not about how many but rather how you prioritise). So the spectre of ‘segments of one’ leaves us scratching our heads – an existential crisis for those of us who get paid to package the market up into somewhere between 4 and 12 homogenous groups; and paralysing for clients who now have (pick a big number) a million segments of one. But is it? And what does ‘segments of one’ actually mean?

In trying to get our collective heads around ‘segments of one’ we keep coming back to the difference between segmentation and profiling – traditionally profiling leverages a mass of data to add flesh to the bones of a segmentation – the segmentation has distilled the complexity inherent in all markets down to something manageable. But, so the argument goes, the processing power of IT, and the ability for brands to now get much closer to their customers etc. etc. makes the segmentation step ‘redundant’ as we no longer need to distil complexity, but rather embrace it. This is the hyperpersonalization argument.

In a piece for ‘Think with Google’ Unilever’s Chief Marketing and Communications Officer, Keith Weed, cited the mobile phone as the driving force behind an empowered consumer – who could disagree – and that its now “driving a hyper segmentation revolution”, and Unilever to “a future where we will build brands in segments of one”.

So let’s think about this in terms of a company that makes things. If my business is making ‘things’ at scale – physical mass customisation or hyperpersonalization is very difficult to do. Scale is important – if I make high spec bicycles, I could customise these to individual taste, but I might make 10, 100, 1000, 5000 a year. What if I make 20million units of something? Whether we are trying to develop strategy or drive something like NPD – we still need to distil complexity into something manageable and useful. Of course Keith Weed isn’t suggesting (I think) that using hyper segmentation Unilever is going down a mass customisation route.

The reality is that we will still have between 4 and 12 segments to allow us to pragmatically manage the complexity and develop our product portfolio and core brand foundations BUT within those segments – data and the ability to now have a one-to-one dialogue with consumers will develop a unique brand experience. Not necessarily one that the brand owner controls but still we can see this one to one relationship as ‘segments of one’. So for a standardised mass market product we may develop individualised brand conversations but we are limited by the nature of the product and the way we go to market. Organisations like Unilever are (it would seem – I have no direct knowledge) looking to developed one-to-one relationships with their consumers – off the back of a mass market product offer. Is this based on profiling within an existing segmentation frame – sort of tactical hyper segmentation within a segmentation? So what is the ‘segment of one’? It is a question of both capability and practicality.

But what about those organisations whose products are intangible …. say Netflix or many financial services companies … companies that can be characterised as having a lot of data on each individual customer and the ability to reconfigure their product offer in an (effectively) infinite number of ways. So they can ‘just’ profile their customer and offer suitable, customised packages (enabled by technology) – they don’t need the intervening step of a consolidating segmentation. Right? Probably not. We are getting much better at trawling data for attitudinal and behavioural cues, and using this knowledge to inform marcoms and other interactions but, to inform strategy, I will bet these organisations are still using some kind of consolidating framework (anyone from NetFlix, please feel free to set me right). Managing complexity is expensive. To embrace complexity to the extent that segments of one would dictate, means redefining what we mean by ‘strategy’. If traditionally strategy has equated to ‘making choices’ – in this new world, the choices are no longer made by the organisation, but rather by the customer. This also assumes that the organisation is less resource constrained – presumably this is a function of technology.

Even as we get better at mining the increasing amounts of data available to us, there is still a long way to go in terms of maximising the value and utility to the customer of this kind of profiling. NetFlix’s ‘Top Picks For …’ seems to me to be little better than random choice – based on watching an episode of 70’s British sitcom Porridge, the recommendation that I might like to watch Top Gear would seem a tenuous link (to me … and that’s the whole point).